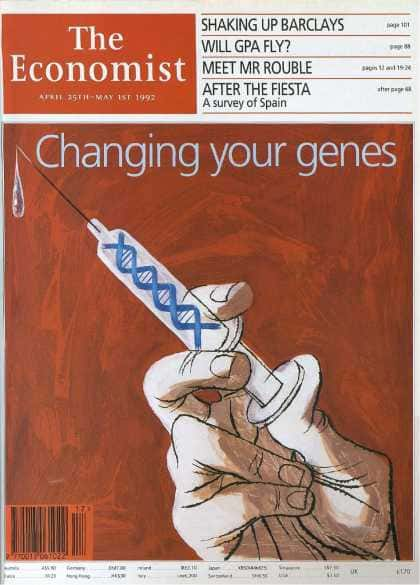

The Economist April 1992

Here is the text to the cover article.

Changing your Genes (1992) The Economist

by The Economist

Topics:

Genes, The Economist, Genetic Engineering, Biomedical ethics

Collection

Opensource:

Changing your Genes. – The Economist. 25 April 1992

1992 Apr 25; 323 (7756):11-12. PMID: 16001470

Genetic Engineering should be Unrestricted. – In: Biomedical ethics: opposing viewpoints. Terry O’Neill, ed. – San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 1994, p. 270-274.

Biology is destiny.” Though the years have been unkind to Sigmund Freud’s thought,

that notion sounds fresher now than when he said it.

In the 1950s the threads of destiny were given form when Francis Crick and

James Watson elucidated the double-helix structure of DNA.

In the 1960s the language of genes,

in which the messages stored on DNA are written, was translated biology,

and much else, began to change. Genes are blamed for everything from cancer to alcoholism.

People worry about being made ineligible for jobs

because of disease susceptibilities they never knew they had,

fetuses are aborted because of faults in their genes,

criminals are defined by the bar-codes of their genetic fingerprints.

Gene Therapy

At first glance,

genetic therapy

– the nascent art of giving sick people new genes to alleviate their illness

– looks like the apotheosis of this trend towards reducing human life to a few short sequences of DNA.

But although its advent means people will be talking in the language of genes even more than they already do,

the way they talk will change.

They will not be passively reading out the immutable genetic lore passed down from generation to generation.

They will not be receiving orders; they will be giving them.

The birth of genetic therapy marks the beginning of an age,

in which man has the power to take control of his genes and make of them what he will.

At the moment, gene therapy is a small field on the fringes of medicine and biotechnology.

Genes carry descriptions of proteins, the molecules that do most of the body’s work;

if someone is missing a gene, they will be missing a protein,

and may thus suffer a deficiency or disease.

If a gene or set of genes runs amok, cancer can result. The gene-therapists aim to provide the body with genes to make good its deficiencies and problems.

If their field had grown as fast as the stacks of ethical reports and regulatory procedures that surround it,

it would already be big business.

As it is, after years of discussion, it is only now starting to blossom.

Therapies are being tried on people around the world (though in tiny numbers)

and new ways of delivering genes are being devised.

A torrent of raw material for tomorrow’s therapies is flowing from the human genome programe,

which plans to have a description of every gene and every scrap of DNA

found in the body by the early years of the next century.

Many hear echoes of eugenics at every mention of the gene, and look at this progress with fear.

Present research,

though,

provides no cause for alarm,

just an occasion for the routine caution with which all medical advances must be treated.

From one point of view, gene therapies are transplants;

from another, they are just drug treatments with the added twist that the drug is being made inside the body.

Experimental gene therapy has satisfied regulators оn that count, so far.

“So far,’ though, is only the beginning,

Beyond today’s gene therapy, which is a specialised form of medicine not that dissimilar to others,

lie far more controversial possibilities:

changing genes for non-medical reasons,

and changing genes wholesale in such a way that the new genes are passed on from generation to generation,

At present, therapists aim at genes that are clearly villains,

and the therapies last at most as long as the patient,

and often only as long as a transient set of cells.

But what of genes that might make a good body better, rather than make a bad one good? Should people be able to retrofit themselves with extra neurotransmitters, to enhance various mental powers? Or to change the colour of their skin? Or to help them run faster, or lift heavier weights?

Humans Make Choices

While the dilemmas of genetic research give many reasons to pause and reflect,

they do not justify slowing or stopping the research itself.

In many cases, the best way to eliminate dilemmas – and protect human life – is to push back genetic frontiers. Admittedly, there are risks involved. The more we master genes, the more options – many of them morally questionable – we will have. But making choices, after all, is what being human is all about.

Joel L. Swerdlow, Моя Quarter, Spring 1992.

Yes, they should. Within some limits, people have a right to make what they want of their lives. The limits should disallow alterations clearly likely to cause harm to others.

Even if the technology allowed it, people should not be allowed to become psychopaths at will,

or to alter their metabolism so that they are permanently enraged.

Deciding which alterations sit in this forbidden category would have to be done case by case,

and in some cases the toss may be passionately argued.

But so it is with all constraints on freedom,

Minimal constraint is as good a principle in genetic law as in any other.

People may make unwise choices. Though that could cause them grief, it will be remediable.

That which can be done,

an be undone people need no more be slaves

to genes they have chosen than to genes they were born with.

To keep that element of choice, however, one thing must be out of bounds.

No one‚ should have his genes changed without his informed consent;

to force genetic change on another without his consent is a violation of his person,

a crime as severe as rape or grievous bodily harm.

There may be subtle social pressures to choose certain traits;

but there is often social pressure for all sorts of things,

and it does not deny the subject free will.

God and Nature

Some will object, in the names of God and nature,

Religious beliefs may strongly influence people’s decisions about what, if any, engineering they undergo.

They should not be allowed to limit the freedoms of unbelievers,

In that it uses natural processes for human ends, gene therapy is as natural, or as unnatural, as most medicine.

But even the artificial carries no moral stigma, The limits imposed by nature are practical, not moral. The body does not have infinite capacities – gains in one ability usually mean losses in others.

Natural selection always seeks to fit the balance of abilities to a given environment,

and abilities it has optimized may prove hard to enhance.

Substantial improvements in human intellect, for example, may not be possible using genes alone

All this refers to the engineering of cells in the bulk of the body,

“somatic” cells which pass no genes to the next generation.

But to influence the early development of embryos, or to create radically different types of persons,

requires a different approach, one that puts new genes into all cells – including the eggs and sperm,

whence they can launch themselves into the next generation.

This sort of “germ-line” therapy, with its long-term effects,

brings to mind spectres of master races and Untermenschen that limited cell therapy does not.

One response to these worries, used by many scientists in the field,

is to say that germ-line therapy is not an option.

Prospective patients may disagree.

Some conditions, which do their nasty work on small embryos,

may for all practical purposes be treatable only by using germ-line therapy.

As yet, no therapy for such conditions has been devised.

If it is,

it would not necessarily be ruled out but it would be right to regulate it far more closely than regular,

somatic-cell therapy.

Germ-line therapy ‘would be similar to major surgery on an unborn child incapable of informed consent,

In such cases, it is commonly accepted that the parents are justified in acting in the child’s interests.

If they can show they are undeniably doing so, there similarly seems no ground for denying the gene therapy.

But that undeniable interest will have to be the avoidance of a clear blight that would prevent the child,

if not treated,

from ever being able to take a similar decision about its future.

If somatic-cell therapy becomes: common,

if biological understanding becomes far more profound,

and if people show an abiding interest in transforming themselves,

then a less conservative approach may prevail – not least because people would know that

a child with genes foisted on it by its parents might be able to change them itself,

come the time.

In such a world, changing children may look less worrying: or it may look unnecessary,

Not all change is genetic.

Surgery can transform people too, as many transsexuals will testify;

increasing intelligence may be easier with prosthetic computers than with rewired brains.

The proper goal is to allow people as much choice as possible about what they do.

To this end, making genes instruments of such freedom, rather than limits upon it, is a great step forward. With apologies to Freud, biology will be best when it is a matter of choice.